Aero Handbook: Difference between revisions

Ahossain45 (talk | contribs) Whale fins added under vorticity in aero handbook |

Ahossain45 (talk | contribs) mNo edit summary |

||

| Line 165: | Line 165: | ||

[[File:TipVortices.jpg | 400px | center]]<br> | [[File:TipVortices.jpg | 400px | center]]<br> | ||

Top vortices form at the ends of wings and are caused by the pressure differential on either side of the wing. Air wants to move from the high-pressure side to the low-pressure side. In doing this, it curls around the end of the wing, creating a vortex. These reduce lift and increase drag. | Top vortices form at the ends of wings and are caused by the pressure differential on either side of the wing. Air wants to move from the high-pressure side to the low-pressure side. In doing this, it curls around the end of the wing, creating a vortex. These reduce lift and increase drag. | ||

==Aerodynamic Tools== | ==Aerodynamic Tools== | ||

| Line 215: | Line 207: | ||

====VGs on Undertrays==== | ====VGs on Undertrays==== | ||

[[File:VGsOnUnderTrays.jpg | 400px | center]]<br> | [[File:VGsOnUnderTrays.jpg | 400px | center]]<br> | ||

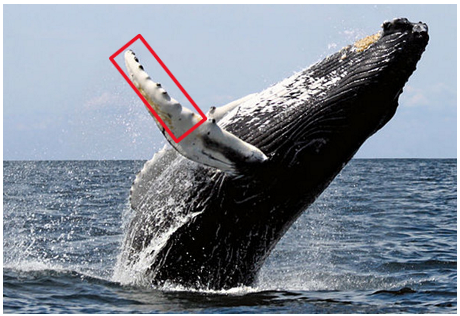

==== Whale Fins ==== | |||

[[File:Humpbackwhalefins.png|center|thumb|400x400px|Humpback whale fins]] | |||

<br>Humpback whale flippers have bumps along their leading edges, known as tubercles. These evenly spaced tubercles create small vortices across the flipper (sometimes called a vortex layer or micro vorticity). By creating a similarly bumpy profile on the leading edge of the UT, we can create small vortices along its surface. | |||

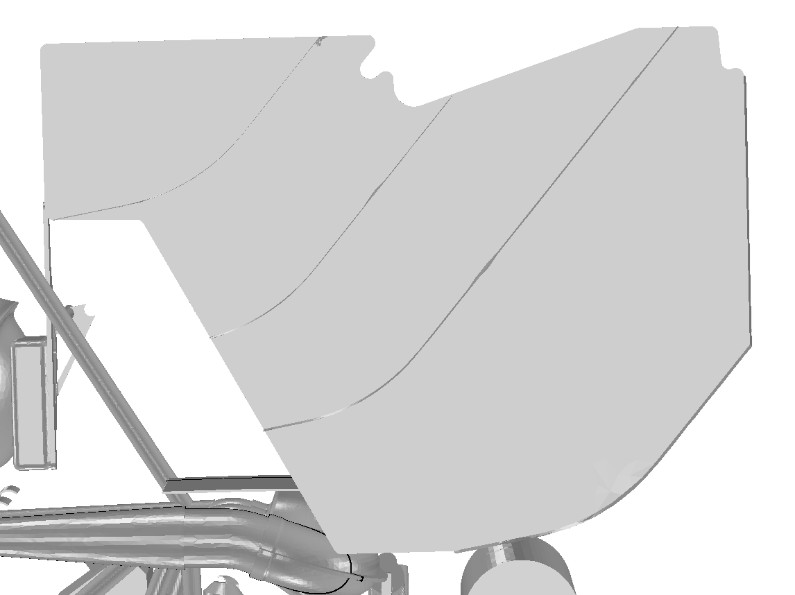

[[File:UTwhalefins.png|center|thumb|400x400px|Undertray whale fins]] | |||

===In-Washing Endplate Vents=== | ===In-Washing Endplate Vents=== | ||

Latest revision as of 11:19, 17 June 2025

Introduction to Sub-Aero

Introduction

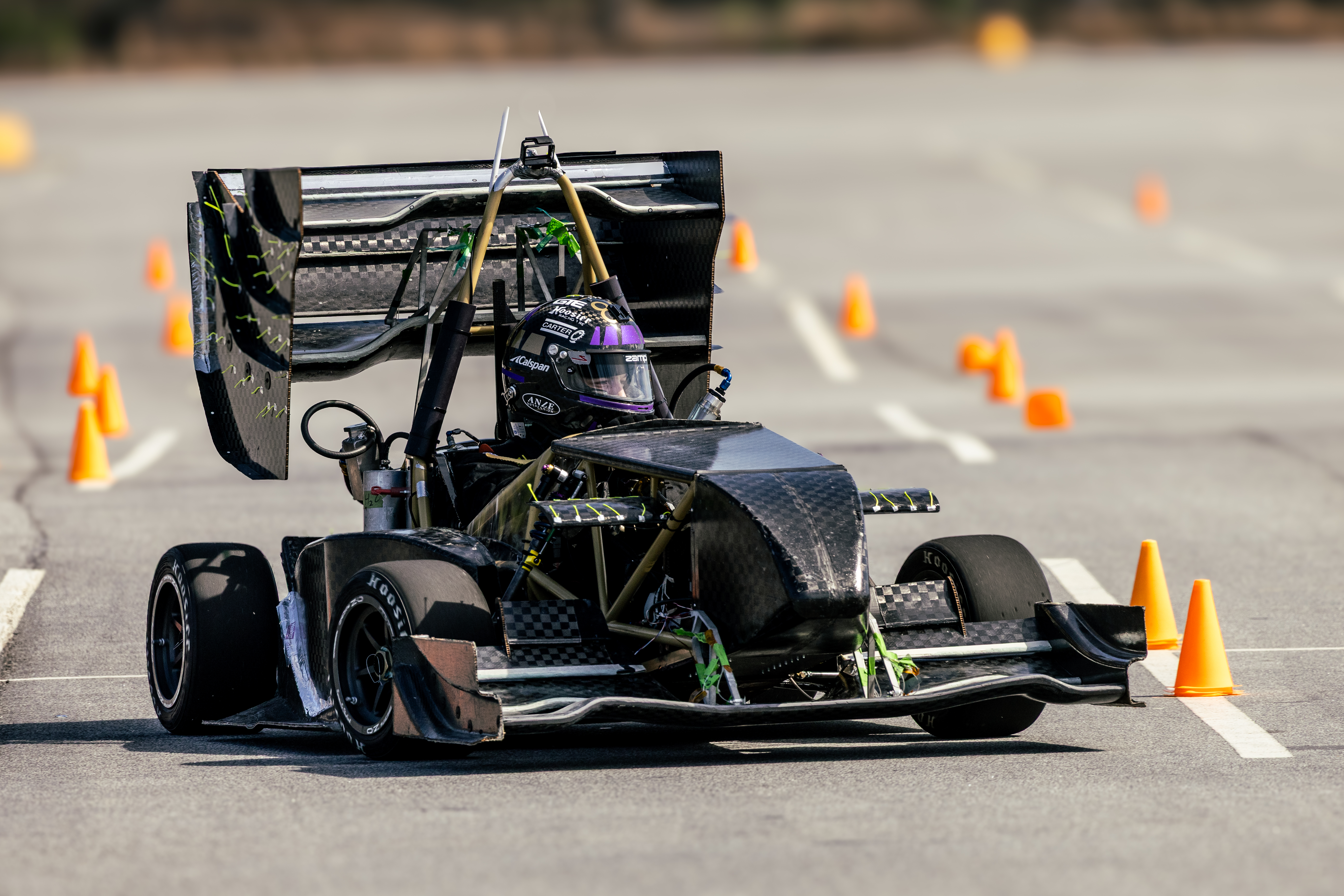

Hello and welcome to the Georgia Tech Motorsports Sub-Aero Handbook! Building race cars is hard, as SuperFastMatt showed with Car 7 . Doing so on a team of students that has completely new members every four years is near impossible. This document intends to make that task slightly less daunting by officially documenting best practices in an organized and efficient manner. While it is impossible to document all the knowledge currently on our sub-system, my hope is to get as close as possible. To future members, please update this. What we consider best practices now are not optimal, and there are far better solutions out there for nearly everything we do. Once you find the better solution, add it, but document what we did prior to avoid regression.

General Sub-Aero terms

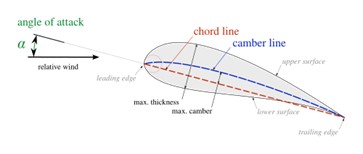

- Airfoil

- The cross-sectional shape of a wing which generates a pressure differential on either side.

- Biplane

- An airfoil or system of airfoils above the main airfoil system in a wing.

- Camber

- The curvature of an airfoil.

- Chord Length

- The distance from the LE to the TE of an airfoil.

- Coefficient

- Normalized, dimensionless quantity describing interaction between a system and fluid.

- Count

- One thousandth of a coefficient. Note: There is no standardized, universal definition of a count, so it is important to define.

- Free Stream

- The state of air infinitely ahead of a given aerodynamic system such that it is not affected by the system.

- Leading Edge (LE)

- The front edge of an airfoil.

- Mainplane

- The first, primary airfoil in a system/series of airfoils.

- Ply

- A layer of fiber in a composite material.

- Ply Schedule

- The construction of a composite skin as defined by individual plys.

- Sandwich Panel

- A composite board made of fibers on either end of a core material.

- Secondary

- The airfoil immediately preceding the mainplane.

- Span Length

- The length of an airfoil along its width (perpendicular its chord).

- Tertiary

- The airfoil immediately preceding the secondary airfoil.

- Trailing Edge (TE)

- The rear edge of an airfoil.

- Up/Down/In/Out Wash

- The movement of air in a respective direction.

- Yaw

- The crosswind experienced by the system, represented by an angle

or

the angular difference in the car’s velocity and wind speed brought on by rotation through a corner. - Core

- The central section of sandwich panel; usually a honeycomb-shaped material or foam.

General Resources

Design Reviews: These are always good places to start, as their real benefit is documentation. Design binders can be helpful as a single document outlines an entire design cycle, but sometimes they are done in different formats. Progress throughout a design cycle should be documented in preliminary, intermediary, and final design reviews. More importantly, these should show concepts that didn’t work and why they didn’t work to prevent repeating mistakes.

Mechanical/Manufacturing Resources

- Easy Composites: Tons of well-made videos on everything composites, including layups and mold design.

- FibreGlast: similar to Easy Composites but in article format.

- Guides and Resources: From our very own Sub-Composites.

- LittleMachineShop: Good source for using metal, including determining what size drill bit to use.

Aerodynamic Resources

- Kyle.Engineers: Former F1 Aerodynamicist turned Youtuber with tons of great videos analyzing different racecars, including an FSAE car.

- NASA: Great introductory articles on different topics in aerodynamics, both theoretical and applied.

- No One Can Explain Why Planes Stay in the Air: An explanation of why we have no concise, physical (non-math based), and general explanation of airfoil theory.

Introduction to Aerodynamic Theory

What We Try to Do

Race cars are built from the tires up; therefore, everything on a racecar is intended to manipulate the tires to make the car accelerate faster. Their grip is a product of the normal force and the coefficient of friction, both of which are constantly changing. Increasing the normal force allows for faster acceleration; however, simply adding mass adds inertial forces that slow the car down. Therefore, we want to increase the force pushing the tires down without increasing mass. There lays the goal of aerodynamics: using the car’s air speed to push it into the ground without adding much mass.

Aerodynamics has two downsides: drag and weight. The package must be designed to work efficiently, meaning the ratio of downforce to drag is high (somewhere between 2 and 3). While we have found an efficiency of 2 to still be beneficial versus having no aero, increasing efficiency can gain many points. F24 has an efficiency of 2.6 and F25 around 2.2. Secondly, as with anything on a racecar, reducing weight directly results in a faster car. F24’s full aero package weighed about 35 pounds; F25’s around 48 (see the lessons learned section for why).

Key Concepts, Equations, and Assumptions

Incompressible Assumption

As with any gas, air is compressible. However, fluid mechanics becomes far more complex with varying density, so a constant density is assumed. At the speeds we run (<70mph), the variation in density is very low. This allows for easier intuition and less computationally heavy simulations.

Steady State Assumption

Steady state means a system does not change with time, whereas transient means it does. Of course, a racecar is constantly changing, so there are transient effects; however, we assume the added computing power needed to simulate transience outweighs the performance gains. Taking a time average of high energy airflow is generally considered accurate.

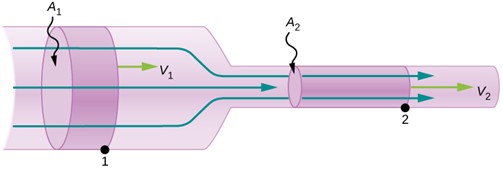

Conservation of Mass

Imagine air passing through a sealed tube. The amount of mass passing through two cross sections of the tube must be equal. This is because mass cannot be created or destroyed. The mass flow, or mass of air passing through per time, at section A1 must equal section A2, giving the equation . Because we assume incompressible flow, the density () may be dropped, and the equation then gives the conservation of volumetric flow in volume per time. To balance the equation, must be greater than because is greater than . Conversely, if were greater than , as in a diffuser, the air would slow down. This equation for conservation of mass may be derived from Reynold’s Transport Theorem if you are interested.

Conservation of Momentum

Newton’s Third Law provides a simple way to intuit aerodynamics: conservation of momentum. For every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction. When the car pushes air up, the air pushes the car down and creates downforce – momentum transfer. This can be derived from Reynold’s Transport Theorem for Momentum, which, for a control volume with one inlet and one outlet at constant density, simplifies to , where F and V are vectors.

For example, take air moving under a wing to be a control volume. Assume the velocity and area at the inlet and outlet of the control volume are the same. As air enters the control volume, it moves horizontally. As it leaves the control volume, it moves vertically. Applying the above equation with the given assumptions means forward and up, so the force acting on the wing is down and back, creating equal amounts of downforce and pressure drag.

Bernoulli's Equation

Bernoulli's Constant

Bernoulli’s Equation relates speed to static pressure along a streamline, or the path of an air particle. We assume variations in the gravity term to be negligible. Bernoulli’s constant is the total pressure along a streamline. To balance the equation, pressure and velocity must be inversely proportional to each other; therefore, as one increases, the other decreases. In the pipe example above, the pressure at point 2 would be less than the pressure at point 1 because velocity increases from point 1 to point 2.

Types of Pressure and Force

Bernoulli's Equations may be expressed as:

Static Pressure + Dynamic Pressure + Gravitational Pressure = Total Pressure

- Static Pressure

- Static Pressure is what we measure as acting on surfaces and is what creates downforce. It can be directly measured with pressure taps with inlets normal to airflow, such as sticking through a surface, normal to it.

- Dynamic Pressure

- Dynamic Pressure is the pressure associated with the movement of air and represents kinetic energy. It can be measured through a pressure tap oriented tangent to airflow. Think if it as the pressure a wall perpendicular to airflow would feel as air particles constantly collide with it, transferring their kinetic energy to the wall.

- Gravitational Pressure

- Gravitational Pressure is pressure due to the depth of the fluid. Because air is light and the change in elevation is very small, we often ignore variations in gravitational pressure.

- Body Forces

- A body force acts on the entire fluid. Gravity or magnetic forces are examples of a body force.

- Surface Forces

- This is what we care about. These act on the surfaces against the fluid, such as a wing.

- Lift

- The component of the aerodynamic force pushing the system up. In our case, lift is negative

- Pressure Drag

- The component of the aerodynamic force, excluding skin friction, which pulls the system backwards.

- Skin Friction

- The shear force between the boundary layer (defined below) and respective surface, slowing the air down and leading to drag.

Putting it All Together: How a Wing Works

A clear, intuitive, physical interpretation of how wings work is surprisingly difficult, and many common explanations are wrong or misleading. While we have been able to model lift mathematically, an intuitive explanation is still under debate.

A leading intuitive explanation states that air molecules begin by moving tangent to the airfoil surface. As the surface curves downward, the tangent motion of the air creates a vacuum, pulling the molecule back down to the wing and causing it to follow the airfoil’s shape again. This explanation accounts for the conservation of momentum, by turning the air, and the cause of the low-pressure region. It also states the high velocity seen on the low-pressure side is simply a byproduct of the lower pressure, rather than the cause of low-pressure, based on Bernoulli’s principle. However, this theory does not account for why flow separation occurs – if the tangential motion creates a vacuum, wouldn’t aggressive curvature just create a stronger vacuum which pulls the molecules to the surface with increased force?

This Article gives other theories and explains the difficulty of finding a concise and general theory.

Incorrect Airfoil Theories

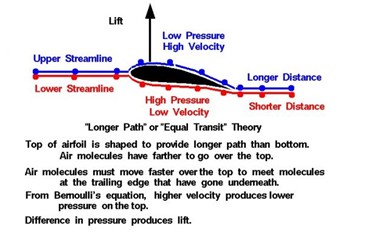

Equal Transit Theory

Described in this article, the Equal Transit Theory states two molecules hitting the LE at the same time will meet at the TE at the same time. Therefore, the molecule moving along the longer side must travel at a higher speed and, according to Bernoulli’s Principle, create lower pressure. However, symmetric airfoils or angled flat plates create lift, which this theory does not explain. Furthermore, the assumption the two molecules meet at the TE is unfounded.

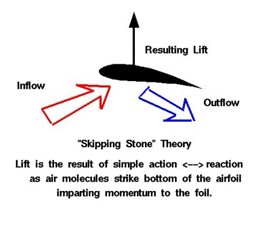

Skipping Stone Theory

The skipping stone theory states molecules colliding with the high-pressure side of an airfoil impart their momentum to the airfoil, generating lift. This theory completely ignores the low-pressure side, which we know is responsible for the bulk of the lift generated. This is further described in this article.

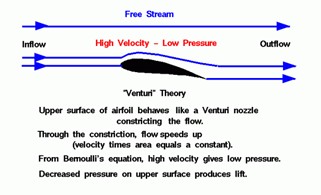

Venturi Theory

The Venturi theory, described in this article, claims air is squeezed at the leading edge causing the airfoil to act as a narrowing pipe. As the “pipe” narrows, it speeds up the air due to the conservation of mass and, according to Bernoulli’s Principle, creates low pressure. However, this still does not account for flat airfoils, like an angled plate creating lift. Further, the assumption that air is constricted to create the pipe effect is unfounded.

Other Aerodynamic Phenomena

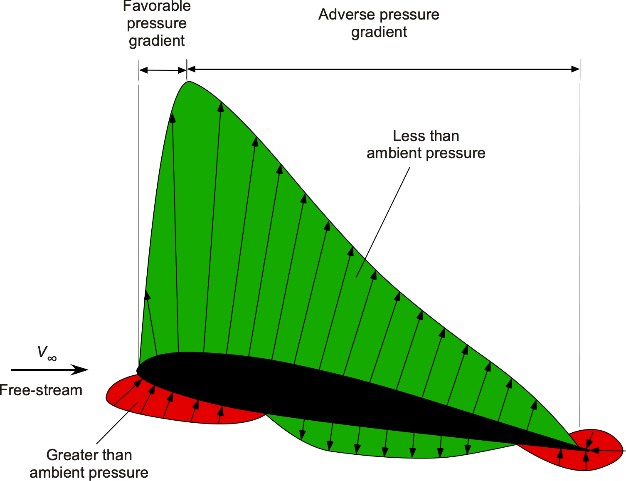

Adverse Pressure Gradients and Flow Separation

An Adverse Pressure Gradient means air flows from low to high pressure. The upstream pressure peak seen on airfoils and diffusers generates such flow. Flow energy is necessary to overcome adverse pressure and allow molecules to follow the surface’s shape. Flow separation occurs when the air does not have enough energy to overcome the relatively higher pressure, causing it to detach from the surface and expand the boundary layer. This image shows gauge pressure, such that the green is negative gauge (relative) pressure and decreasing magnitude represents an increase in absolute (gauge + atmospheric) pressure.

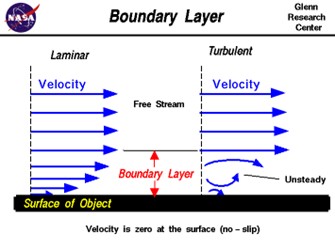

Boundary Layers and the "No Slip Condition"

The No-Slip Condition states that the infinitesimally thin layer of air in contact with a surface has no relative velocity to the surface – that is, the air sticks to it. Moving further from the surface, the air slowly approaches the free stream velocity.

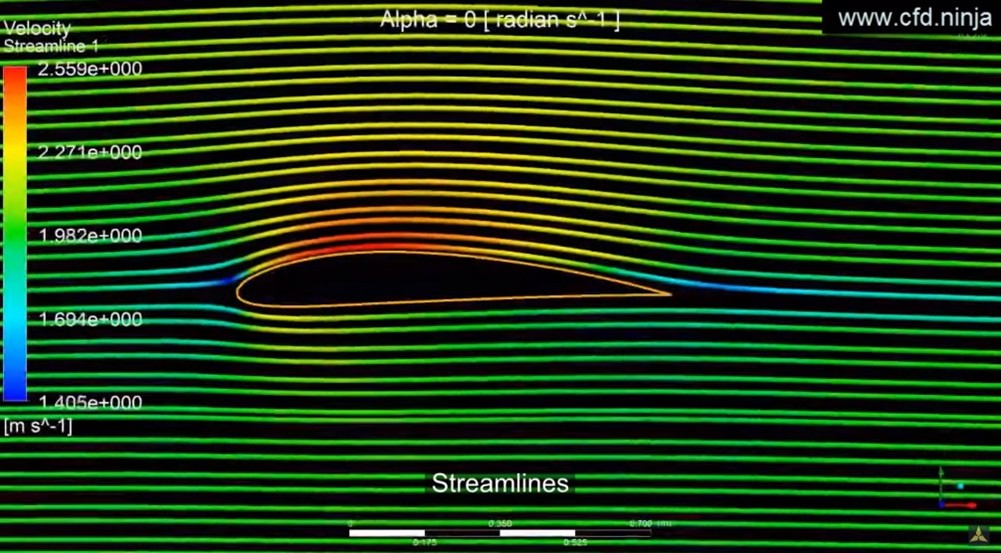

Laminar Versus Turbulent Flow

Laminar flow follows very smooth, predictable streamlines whereas turbulent flow is unsteady and unpredictable. Turbulent boundary layers, however, have much better flow attachment due to their higher energy. The region between laminar and turbulent flow is called transitional, but is not important for us.

Flow Detachment

Flow Detachment occurs when the curvature of a surface is overly aggressive such that the boundary layer grows very large and turbulent, preventing the air above from following the surface’s shape. This is also called stalled airflow. Because downforce is generated by turning the air upward, air not following a surface’s shape prevents downforce generation. The stalled air generates vortices, or eddies, which in turn generate drag.

Vorticity

A vortex is an aerodynamic structure rotating about a line, such that the air has very high angular velocity. In the center, the line or point has very low pressure which constantly pulls the air in; however, the air’s linear momentum prevents it from reaching this low-pressure point. These effects result in a stable, low-pressure, high energy flow structure.

Vortex Characteristics

- Low Pressure: Vortices generally create low-pressure regions. Vortices forming along the low-pressure side of an airfoil can create additional lift or downforce.

- High Flow Attachment: Vortices cling to surfaces better than laminar airflow such that they support flow attachment. This is due to their high energy.

- High Drag: Vortices generate high amounts of drag due to the high energy they take to form.

Tip Vortices

Top vortices form at the ends of wings and are caused by the pressure differential on either side of the wing. Air wants to move from the high-pressure side to the low-pressure side. In doing this, it curls around the end of the wing, creating a vortex. These reduce lift and increase drag.

Aerodynamic Tools

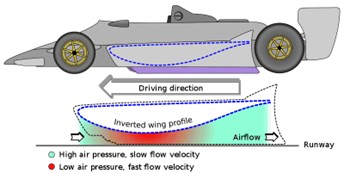

Airfoils

An airfoil is the cross-sectional portion of a wing, shaped to create a high- and low-pressure side. For a downforce generating airfoil, the bottom side is low pressure as it sucks the wing downward.

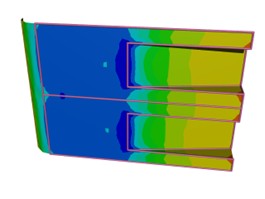

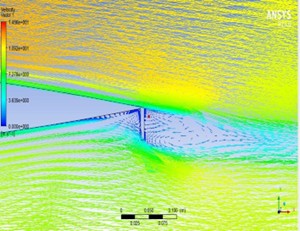

Diffusers

Diffusers suck in air, driving high speed flow at their inlet. Conservation of mass requires air to slow through the diffuser as its cross-sectional area increases. This image shows the pressure across the diffuser’s surface. The diffuser sucks air from the floor, driving high speed flow across the flat bottom. Because Bernoulli’s Principle states high speed flow creates low static pressure, the floor experiences low pressure, as shown by the blue. The diffuser inlet experiences the highest velocity – this effect can be seen by the deep blue pressure peak. As the air travels through the diffuser and slows down, the pressure map shows increasing pressure.

For a more intuitive understanding, conservation of momentum may still be applied: the diffuser gradually turns the air upwards, so the air must impart a reactionary force downward on the car.

Venturi Tunnels

While similar to diffusers, Venturi Tunnels squeeze the air at the inlet to create a stronger pressure peak. The inlet collects air and then forces it through a choke point before it is sucked and expanded through the diffuser. Venturi tunnels generally have stronger performance than simple diffusers but are more complex to design and may require a longer chord length.

An intuitive reason they create more downforce than a diffuser is because the lower suction peak draws in more air, generating more momentum transfer as more mass flow is accelerated upward.

Endplates

As previously discussed, wings generate tip vortices due to the pressure differential on either side. These vortices cause high drag and reduce downforce, so preventing them creates a better wing. Endplates help accomplish this by preventing airflow at the wing’s tip from the high-pressure side to the low-pressure side. Without this airflow, the vortex does not form. Oversized endplates experience poor yaw performance and limit the amount of air the wing may affect, thus limiting downforce generation.

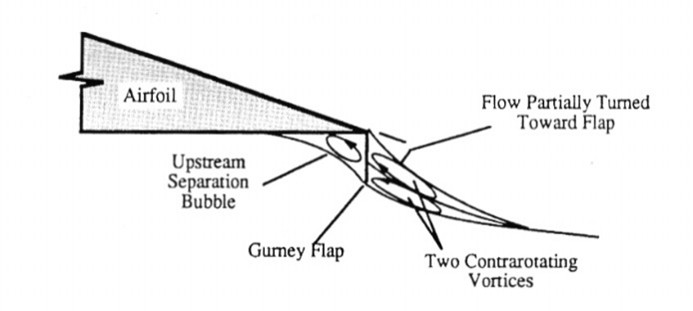

Gurney Flaps

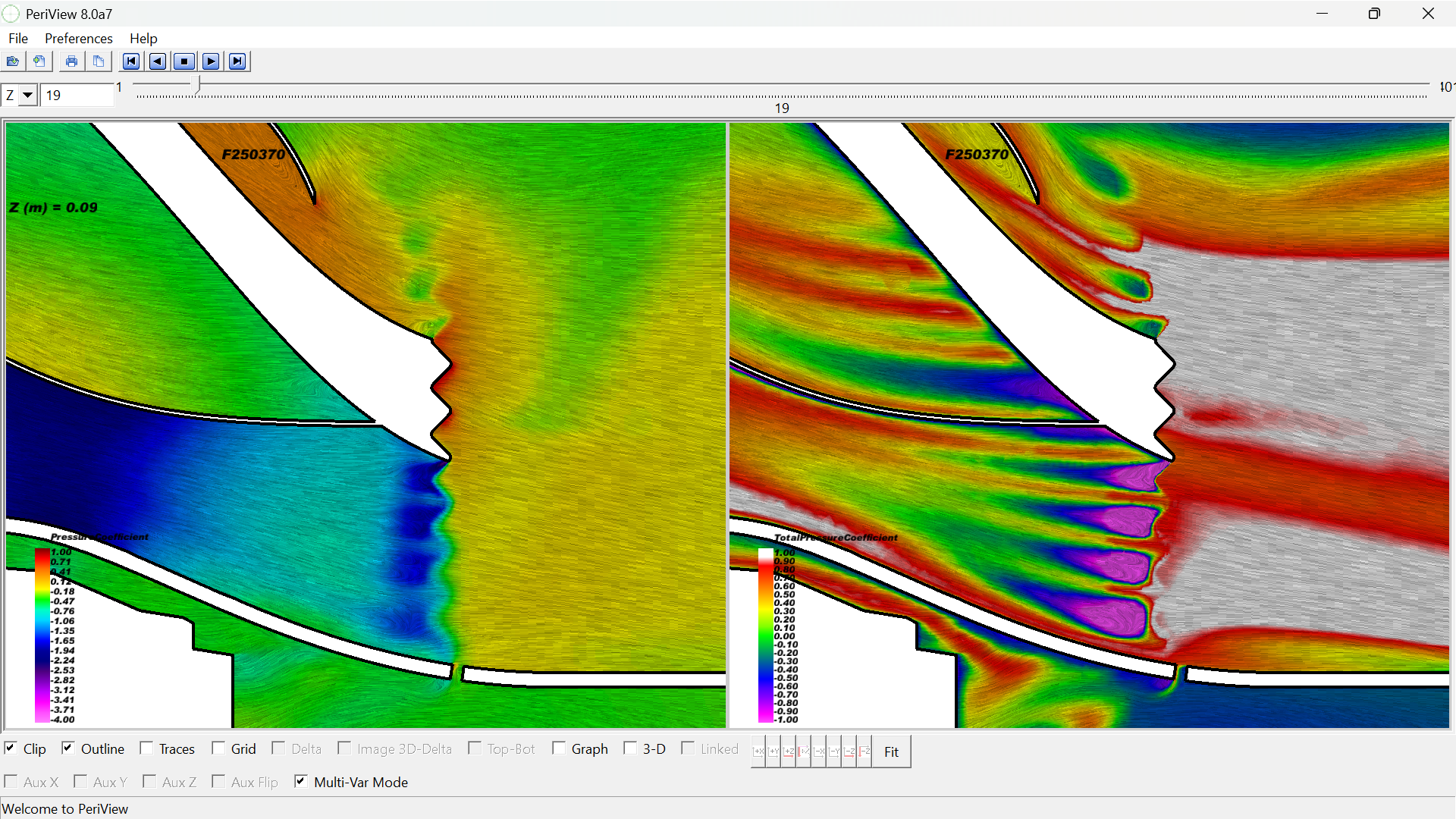

Gurney Flaps are small, flat plates at a wing’s trailing edge oriented normal to the chord. They create a turbulent region behind them. The air comes off the wing and continues flowing smoothly along the border of this region, making the unsteady region act as an extension of the wing. This may be seen on the second image, where the boundary layer – the green portion along the surface – continues along the grey region behind the Gurney Flap.

Gurney Flaps effectively increase the chamber and chord length of an airfoil while supporting flow attachment. Downsides include large drag generation due to the turbulent flow they cause.

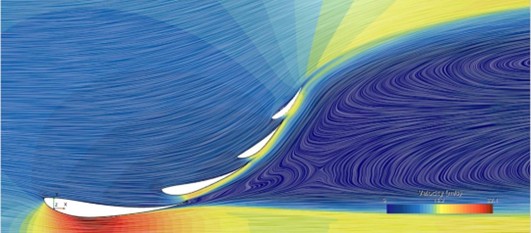

Slot Gaps

As previously discussed, flow detachment occurs when the boundary layer does not have enough energy to continue flowing through the adverse pressure gradient. Slot gaps delay flow attachment by injecting high energy flow into the boundary layer. The image above shows flow detachment near the TE of the first airfoil, indicated by the blue flow which doesn’t follow the upward curve of the TE. However, after the slot gaps there is high speed flow following the curvature of the secondary airfoil, showing strong flow attachment.

Vortex Generators

Vortex generators are another way to promote flow attachment by injecting high energy flow into the boundary layer. They can also be thought of as blocking the existing boundary layer while mixing in freestream air.

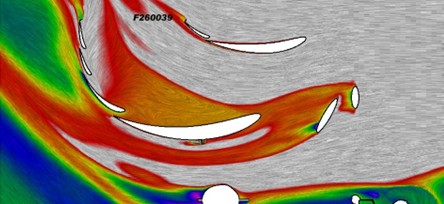

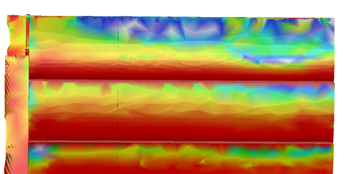

VGs on Airfoils

The image above is a total pressure plot of a rear wing. Total pressure is a way to visualize flow energy and therefore boundary layers. The red indicates lower energy and white/grey high energy. The black circle features a vortex generator. Prior to the VG, there is a clearly stressed, red boundary layer; afterwards, there is a high energy, white boundary layer.

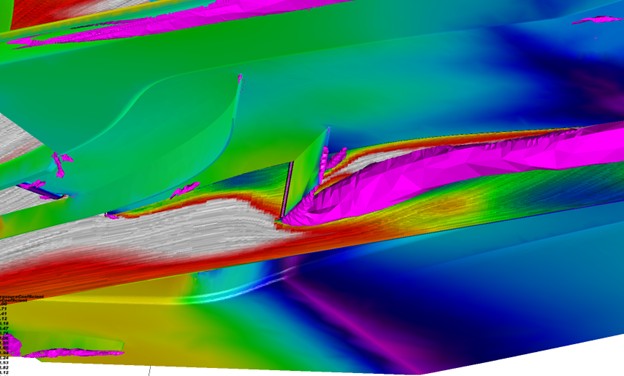

VGs on Undertrays

Whale Fins

Humpback whale flippers have bumps along their leading edges, known as tubercles. These evenly spaced tubercles create small vortices across the flipper (sometimes called a vortex layer or micro vorticity). By creating a similarly bumpy profile on the leading edge of the UT, we can create small vortices along its surface.

In-Washing Endplate Vents

In-washing vents are holes in the endplate which allow ambient air flow into the low-pressure region below the airfoil, promoting flow attachment at the expense of air expansion.

The top image shows two of these vents on F26’s RW endplate

The lower image shows a shear stress (skin friction) plot from the perspective of standing behind the car looking forward. High shear stress indicates strong flow attachment. The circled region is immediately inboard of the endplate vent and exhibits higher shear stress than the segments toward the center of the wing.

Design Methods

Goal Setting

FILL THIS IN

Integration

Having aero in FSAE is often looked at as a nice to have. This makes it easy to get pushed around.

- Set up integration bounding boxes early in the design cycle. This gives a clear space to work in. If someone breaks this agreement, you have something to point to.

- Catch things early. If some interference between parts gets caught in manufacturing, aero almost always is the one to end up cutting. Constantly check for interference with other sub-systems in CAD during design and ensure you are using accurate and updated references. Ask respective leads if the CAD is correct. Once again, doing so will give someone to point to if their CAD ends up being wrong. 38’s undertray has holes for the lower control arm, upper control arm, exhaust, and oil pan because nobody checked CAD.

- People like numbers. A failure of 38’s design cycle was not giving other sub-systems data to show why we wanted certain integration points – hence reverting to the front dampers being mounted on top of the nose.

CAD

Aerodynamic Design

Aerodynamic design utilizes a variety of CFD cases to meet design requirement. These cases simulate the car in several conditions, such as straight line, cornering, crosswind, etc. to mimic on track scenarios. An iterative process may be used to create a design, simulate it, interpret the results, and create a new design.

Computation Fluid Dynamics (CFD)

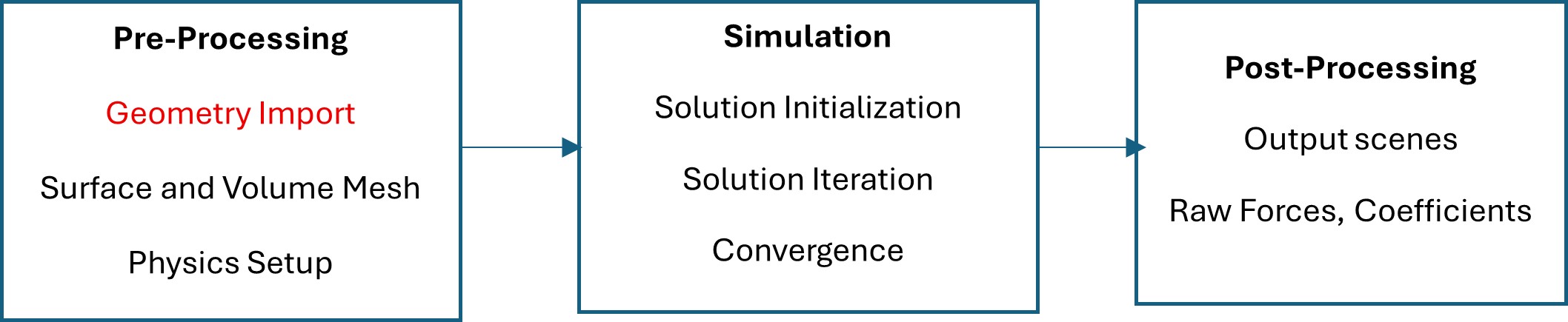

Oooooh boy, aren’t you excited to run your first CFD! First off pal, you don’t “run a CFD”, you run a sim, so that’s strike one. So you don’t use up your other two strikes and blow up our sim computers, here’s some detailed instructions on our CFD environment setup, automation, and use. Below is a workflow of the process used in completing a CFD simulation. In red are the parts that are not currently automated by the sim queue.

“Pre-processing” (Geometry Preparation, Meshing, Physics Setup)

Geometry Preparation

How do we begin the simulation process of an aerodynamic part? We first look to the part itself in CAD. There are some rules of thumb that should be followed for all aerodynamic parts that are to be imported into CFD and ran in a simulation.

- Sharp Edges: Avoid geometry with any sharp edges. The rule of thumb in this case is not to create an edge that has a thickness of less than two millimeters. If that sounds like a lot, go outside to whatever car is in shop now and measure the thickness of the trailing edge. Not only are sharp edges impossible to achieve on car, they cause issues with the mesh. More gory details in the mesh portion of this section, but in layman’s terms your surface will become a big grid, and when the grid is touching (like at a sharp edge) bad math things happen and your sim gets sad.

- Closed Surfaces: Either one of two types of bodies should be used inside of a CFD simulation. Solid bodies work well, as they will behave as just that, a surface with a closed-out region. The second type is a surface that has either been thickened or closed entirely. Do not use a lone surface body in a CFD sim. This essentially acts as a really long sharp surface. You can check if your surface is closed if you are given the option to make it a solid body when you knit the final part together.

- Export Type: Export your parts as parasolids (.x_t). Our software reads these geometry files best. STEP files may also be used.

Meshing

Meet Siemens Simcenter STAR-CCM+, the official name of our CFD software. Most referred to as star, this software is industry standard for automotive aerodynamics. You might hear a ton about meshing jargon from those in industry or otherwise because of how important it is to get right for a correct simulation. Don’t worry, this section discretizes the most important things to get right about your mesh.

Before that, though, the user should understand that star (or at least our use of it) utilizes an automated mesher. There is software dedicated to creating custom meshes from scratch like pointwise. The automated mesher in star is highly customizable and renowned for it’s ability. We should be fine.

- Cell Density

- The most obvious parameter to adjust in you mesh is your cell density. Lower densities will allow for faster solutions but finer meshes will be more accurate. A “mesh convergence study” of sorts was conducted a while ago which allowed us to land on our current density settings. Truth is, though, we make the cell density as small as possible where we can without sacrificing accuracy. No exact math here, just be mindful of reducing cell density in aerodynamic parts

- Y+

- is a dimensionless distance from a solid wall to the first computational grid cell in a CFD simulation. It normalizes this physical distance by the viscous length scale, which is crucial for accurately capturing flow behavior within the boundary layer.

- For k-omega turbulence models, especially the k-omega SST model, the choice of is critical because these models are often designed to directly resolve the viscous sublayer. This typically requires a very low value, ideally around 1, meaning a fine mesh near the wall. If is too high when using these models without appropriate wall functions, it can lead to inaccurate predictions of flow separation and wall shear stress.

Interpreting CFD Results

CFD, and simulations and tests in general, have two categories of outputs: qualitative and quantitative. Qualitative includes graphs and other non-numerical data. Quantitative is strictly numerical and objective. Qualitative CFD results are pressure maps of the car's surface or surrounding airflow, while qualitative results include parameters such a or CoP. Below are several important outputs to interpret CFD results:

- Pressure Coefficient

- This gives normalized static pressure – what actually acts on the aerodynamic surfaces to create lift or drag.

- Skin Friction Coefficient

- This gives normalized shear stress. In fluid mechanics, shear stress is the stress acting between layers of a fluid or between a surface and the fluid. High skin friction is indicative of strong flow attachment.

- Total Pressure Coefficient

- This gives a normalized sum of static and dynamic pressure and may be used to interpret the total energy in the fluid. The total energy is helpful in understanding whether a wing is receiving clean airflow or whether a boundary layer is attached.

- Velocity

- While helpful in understanding the flow field, velocity is included in the total pressure coefficient and has a strong correlation with pressure, so looking at velocity on its own may not always be helpful.

Mechanical Design

Structures matter. Don’t leave the mechanical side of the design cycle for the last minute. Taking time to put thought into how everything fits together will result in a far lighter and resilient package and likely be easier to deal with.

We currently use a composite rib and spar structure. The spars are made of 3-core-3 sandwich panel with 0.25in Nomex core. Ribs are a mix of this sandwich panel and various types of aluminum, as outer ribs and mounting ribs must be threaded. Slots allow ribs and spars to intersect. DP-460 is used to glue everything together.

Mainplanes have a bulkhead. The front wing’s is to protect against cone strikes and the rear’s is mainly for easier bonding. Make everything easy to take on and off. Aero’s primary responsibility on drive days and at comp is just removing wings. During design, ensure nothing is too close to the bolts so that they’re easier to remove.

Overview of Fiber Reinforced Composites

Composites structures consist of two materials: a matrix and a reinforcement. In our case, the matrix is epoxy resin and the reinforcement carbon fiber. This is known as carbon fiber reinforced plastic (CFRP). Composites work on the theory that the reinforcement (fiber) has strong tensile properties but lacks rigidity; adding rigidity through the matrix creates a strong, resilient, lightweight structure. However, CFRPs lack significant compressive strength.

In general, for a structural component in bending, the outer edges of the component take the most stress, such that as you go inward of the component, the stress lessens. Therefor, the inner portion carries less load. Sandwich panels use this principle to retain strength while reducing weight considerably. They use a core material, such a Nomex honeycomb, which support the outer skin.

LINK TO COMPOSITES PAGE

Manufacturing Methods

Composites

A comprehensive composites manufacturing guide, including tooling design and manufacturing, can be found in the Composites Wiki Page. INSERT COMPOSITES WIKI PAGE

Waterjet

Water jets use high pressure water mixed with garnet to cut through material. They work well for making accurate 2D geometry and may be used on most materials we work with, including metal and composites. For detailed Waterjet resources, see the Water Jet Page.

Assembly Methods

Fasteners

Fastener Dimensions and Tools

We mainly use three different bolt types: #6-32, #8-32, and #10-32. Sticking to just three bolts lowers costs and complexity. Standard bolts are defined by the bolt number – thread pitch, where the bolt number indicates diameter, and the thread pitch gives the number of threads per inch.

LittleMachineShop gives diameters for through holes and threaded holes for different bolts. The chart below gives dimensions for Aluminum – for other materials, check the link.

| Bolt | Through Hole (Close Fit) | Threaded Hole | Button Cap Hex Bit | Hex Head Size | Hex Nut Size |

| #6-32 | #27 drill bit = 0.1440” | #36 drill bit = 0.1065” | 5/64" | 1/4" | 5/16" |

| #8-32 | #18 drill bit = 0.1695” | #29 drill bit = 0.1360” | 3/32" | 1/4" | 11/32" |

| #10-32 | #9 drill bit = 0.1960” | #25 drill bit = 0.1495” | 1/8" | 5/16" | 3/8" |

| 1/4-20 | F drill bit =0.2570" | 7/32" = 0.2188 | 5/32" | 7/16" | 7/16" |

Note: These are compiled from McMaster and only apply to the specific products linked: 18-8 button cap or hex head.

Composite Fasteners

Attaching fasteners onto composites such that it clamps down is not best practice, but we do it, as it only requires a through hole on the part. Care must be taken not to over tighten the bolt and crush the composite material – larger washers are recommended to disperse the clamping force.

A good check for tightening bolts is whether the washer can move – if it can, the bolt should be tightened more. For larger washers, you can tighten more but stop if the part begins to deform.

Because these bolts must be relatively loose, medium strength thread locker is highly recommended for competition.

Adhesives

Many parts that do not require diss-assembly may be bonded together. As adhesives can act as a lubricant between substrates while curing, bonding jigs are highly recommended. Reference points should be added either to the part itself or the mold to create accurate and precise jigs.

Even application of adhesive is critical to a strong bong. Ensure that the adhesive is in contact throughout both bonding surfaces – failure to do so will result in less bonded area and more stress concentrations. Pressure may be applied to ensure even application alongside jigs.

DP-460 is very expensive and likely overkill for much of what we do, but over kill isn’t necessarily a bad thing for structure-critical bonds. DP-460NS is an extra viscous version of regular DP-460. Thickening agents may also be used to increase viscosity and strength.

Repairing Composite Parts

ADD COMPOSITES PAGE

Small Repairs

Small failures can usually be repaired with just DP-460. Black dye may be helpful. To make a smooth surface out of DP-460, place Kapton tape over it and apply pressure.

Large Repairs

A wet layup with an adhesive such as DP-460 and Kevlar or carbon fiber is effective at reinforcing areas where significant scraping has occurred. Be sure to wet out the fiber fully, as DP-460 is very viscous.

General Advice

Drive Days

Most of Aero’s drive day work is done the day before. While we are unlikely to prevent the car from driving, mistakes in not properly fastening parts or other lapses can easily take up lots of time during testing, or even damage parts.

Packing

Organized packing can save lots of time – we have lots of small parts that look similar, so parsing through them on a time crunch is a pain. Have an organized box of all tools and hardware needed for the package in easy-to-grab format and ensure it doesn’t get cluttered or have items placed haphazardly.

Checks

Take time to ensure all bolts are tightened (but not overly tightened to the point of crushing the carbon). Also take note of any scrape-areas to track damage during drive.

During Drive

If the car is excessively scraping, leads have the authority to pause drive or take aero off. Ride height should be set to the lowest point aero doesn’t scrape excessively.

Competition

FILL IN

Sub-Aero History and Lessons Learned

2024-25 School Year: F25

Leadership

Alex Hammonds, Caleb Kopitsky, Jack Devenish

Highlights

- 4.2 Simulated ClA

- 48lb System Weight

- 330+ Testing Miles

- 1st endurance, 2nd autocross, 3rd overall at Michigan

Lessons

Better CAD Integration

The UT had to have several holes cut for PT and SUS interference which was not caught in CAD at all or caught too late to change.

Vehicle Dynamics Integration

This year has much better integration between aero and VD, leading to the car running much stiffer to prevent roll outside the aerodynamic operating range. We also became responsible for setting ride height.

Package Durability

Over the 330+ miles of testing, the package took lots of damage. The FW endplates, FW central mainplane, and rear corners of the UT all had significant damage. The endplates were remade the week before comp and a DP-460 – Kevlar layup was done on the central portion of the FW mainplane as all but the final layer of carbon has scrapped away.

In areas of severe scraping, such as the FW endplates, two layers of Kevlar may be needed, or a metal plate. Kevlar should also be added to the inboard section of the FW mainplane: under high loading of the endplate, the wing deflects and slams this portion into the ground.

Mold Design

Composites was not consulted for mold design, leading to runoff areas being too short for infusion. This only allowed for wet layups, significantly increasing package weight.

Going forward, composites should sign off on all mold design.

Fiber-Matrix Adhesion

Due to poor adhesion between the fibers and matrix, many parts came of overly compliant. They had to either be remade or have a backing added, wasting time and resources. Other parts had to be made with a heavier weave, twill, with the problem fiber, spread tow, as an extra, cosmetic outer layer.

Going forward, test fiber-matrix combinations before buying them in bulk to prevent such issues.

Design Competition

The judges said “they got through most of other systems knowledge in the first five minutes, but never found the bottom of ours”. Having a breadth of information is very helpful, as judges will ask about a wide range of topics. Don’t bullshit answers: its better so say you don’t know something or don’t have a response than to make something up.

Have more VD data, both simulated and measured: use load cells to calculate Cl/Cd values and measure yaw from rotation.

2023-24 School Year: F24

Leadership

Caleb Kopitsky, Jack Devenish, Owen Patterson

Highlights

- First team outside Germany to complete a rolling road wind tunnel test @ Penske

- Highest measured ClA of 3.8

- Simulated ClA of 3.75, CdA 1.45, Efficiency 2.58

- First year of rib-spar structure

- Engine exploded at Michigan :)

Lessons

Manufacturing Rush

To make the wind tunnel deadline, we had to manufacture ~80% of the aero package in just two months, as it was already behind.

Don’t put the team in a position requiring the package to be manufactured in two months – It fucking sucks.

Invention Studio, Router, and Water Jet Access

We had to rely on other team members outside aero to access the CNC router for molds and the waterjet. This made scheduling difficult and was unfair to those with access.

At least one person should have PI access to the Invention Studio.

Design Competition

Wind tunnel went over very, very well. Aero design judge ended up giving us a perfect score and chassis 3 extra points. He allowed us to run through our presentation instead of breaking it up and asking lots of questions, which he said other design judges are more likely to do.

2022-23 School Year: F23

Leadership

Owen Patterson, Phil Realina